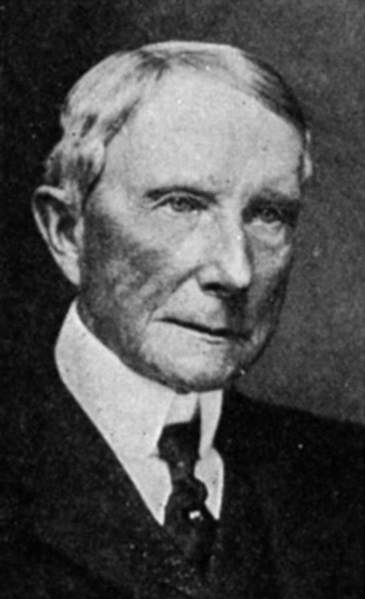

John D. Rockefeller

I am reading TITAN, THEÂ LIFEÂ OF JOHNÂ DÂ ROCKEFELLER by Ron Chernow.

This is a fascinating and absolutely captivating book, but also one with lessons for those of us in the burgeoning video business.

Rockefeller started as a very poor boy indeed in rural upstate New York, but he ended not only as the wealthiest man in the world, but also someone who change and essentially shaped the world we live in today – the world driven by petroleum.

Rockefeller was born into a world, in the 1850s, that was little changed in many ways since Roman times.

Most people still moved things by horse. There was no electricity. People kept this lamps lit by burining a sputtering mix of cheap animal fat and tallow.

By the time he died, the world was far closer to the world in which we live today.

An astonishing transformation.

What made all this possible was the discovery of pools of underground oil, then called ‘rock oil’ by Edwin Drake in 1859.

Drake’s discovery, combined with the work of Prof. Benjamin Silliman, a Yale University chemist who found a way to ‘crack’ crude petroleum to make distillates, forever changed our world. Rockefeller, a young businessman just starting a career in Cleveland, Ohio, saw the potential that the oil business, which had never existed before, offered. And he acted.

What oil did was to unleash vast amounts of power at very low costs. This is something humanity had never encountered before.

Oil is essentially the power of the sun, captured over millions of years and stored up for instant releast. One barrel of oil contains about 5.8 million BTU or the equivalent of 30 horsepower. 30 units of horsepower is the equivalent of the work that 360 men can do. So one barrel of oil being burned is the equivalent of the power that 360 men would be able to achieve through physical exertion – which was how most things were achieved when Rockefeller was born.

The secret to the world in which we live today is, in short, a great deal of energy produced very cheaply.

How long these supplies will hold out is anyone’s guess, but certainly not forever.

Rockefeller, of course, seeing this largely before anyone else, was able to tap into this vast new reservoir of previously unimagined energy at remarkably low costs and change the world. Electricity, automobiles, airplanes, plastics, mass agriculture, shipping, and pretty much everything else we take for granted today was the result.

All of which brings me to video and film (remarkably).

Up until now, our processes for creating content for television and cinema have been the media equivalent of Romans and slave labor – incredibly labor intensive, not at all cost effective and very very limited in scope or quantity.

Take a look at the titles at the end of a film or a TV show for that matter.

19 weeks to produce every hour of television you see.

$250,000 and up to produce each hour of TV and hundreds of millions to produce every 90 minutes of movies.

This is as insane and untenable as plowing a field with a wooden plow dragged by a horse or two. It works, but it is a lot of work for very little yield.

Yet, up until now, this was the only way we understood of creating content, just as everyone in the world of 1850 knew that the only way to illuminate your house after dark was to burn tallow and a wick – or whale oil if you were very very rich. No one sat around saying ‘my God, we live in an absolutely primitive and deprived world of spartan accomodations and technology’. Nope, no one said that. Everyone thought – this is just the way it is.

Yet beneath Rockefeller’s very feet lay millions and milions of barrels of untapped cheap energy.

All around us lay millions and millions of hours of untapped yet cheap content and entertainment.

Just look around you.

What Rockefeller needed was two things – a way to get at it, and a way to process it to be of value.

What we need are the same things: a way to get at it and a way to process or focus it to be of value.

The raw material is there.

I recently had dinner with a friend who owns a sports magazine in the UK based on Cricket.

It’s a very popular sport in England and in much of the world.

He has recently started a website parallel to the magazine, and of course he is starting to think about video.

Here is a Rockefeller-like opportunity.

As we all know, television and the web are about to merge.

Soon you won’t be able to tell the difference between TV networks, cable and web-produced content.

So my friend has a chance to create, in effect, The Cricket Channel.

He can do it cheaply and efficiently – far far far more cheaply than The BBC would do it, and I think if it is done right, with far better and more interesting content.

As the ‘Great Convergence’ happens (probably 2-3 years away), he is going to effectively own this part of broadcasting, and for very little investment.

The potential is all around us. Like John D, we just have to see that it is there.