Today’s killer is tomorrow’s endangered species…

The flight from Los Angeles to Brussels is endless, so it gave me plenty of time to read Snowball,Warren Buffett and the Business of Life by Alice Schroeder.

The book is much more than just the life of Buffett (which is plenty in and of itself), it is also filled with fascinating asides.

One that really grabbed my attention was the history of Berkshire Hathaway, a New England firm that Buffett bought in the early 60s, and whose name became the foundation of Buffett’s empire (though hardly its product). Berkshire Hathaway was a textile mill in an era when textile manufacturing was headed south (literally), abandoning Massachusettes for Georgia and South Carolina, where the cotton was closer and labor was a whole lot less expensive.

The company was based in New Bedford, Mass, which I had no idea had once been North America’s richest city. (Schroeder footnotes extensively, so I assume it’s all true). The wealth of New Bedford had been based on whaling, which was, quite literally, the oil business of the 18th and 19th Century. Whale oil was used to light the lamps that the Founding Fathers of this country wrote the Constitution by, and much beyond. It was the primary source of illumination after dark.

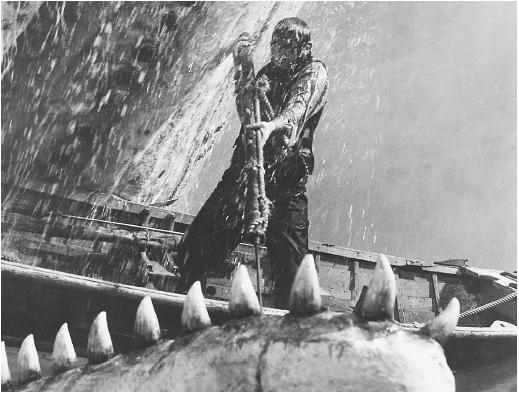

As the market for whale oil expanded, the number of whales nearby began to drop. Ships out of New Bedford had to go further and further – to the Arctic, to the Pacific, to find their prey. And so the ships got bigger and better and faster. And New Bedford grew richer and richer. Think of it as Dallas or Dubai.

Then, in 1859, oil was found under the ground in Titusville, Pennsylvania. And a whole lot of other places after that.

It turned out to be a whole lot cheaper to drill in Titusville than it was to take a ship to the Arctic to achieve the same end – keep the lamps burning at night.

So the basis of the economy of New Bedford collapsed – and so did its ranking as the Richest City in North America.

This might be the end of the story. Yet another example of ‘creative-destruction’ of new technologies. But there is a coda here (actually a coda to a coda), which is what makes the books so interesting.

As the whaling ships grew faster and stronger, it became obvious that they could be used for more than just collecting whale oil. So in 1888, Horatio Hathaway organized a group of investors to pursue what they saw as ‘the next business trend’, and began using the ships to drive the textile trade.

This was not the original ‘core business’ of New Bedford, but textiles soon came to replace whaling as the foundation of New England’s economy.

Now, what does this have to do with video and the web?

First, new technologies, like drilling for oil (and as we’ll see later, air conditioning), can evaporate what seems like a stable business overnight. But if you are smart, and look carefully, the seeds of not only survival but success can be buried in your dying business. You just have to be able to separate yourself from what you perceive to have been the ‘core business’.

Take Newspapers.

A business in serious trouble because of the ‘discovery’ of the web. Like the oil field of Titusville, a cheap, seemingly inexhaustable source of distribution to replace the costly paper, ink and daily trips to the Arctic.

But like the whalers with their ships, the newspapers also own a resource of enormous value: a machine to gather and produce local information. Probably its final destination is no longer paper and ink; it might not even be ‘news’, but the value of the machine should not be lost… rather repurposed.